For some historical context, see Part I of this blog, Putting the Kettle On.

As I was working on the numbers for this blog, the most shocking statistic I came across concerned the annual federal budget. Only five out of the last fifty years have shown a budget surplus, and three of those years were under Clinton. The other forty-five years ran budget deficits. The highest surplus was in the year 2000 when government coffers were $236 billion to the good. So the logical question in any financial analysis of the United States is what did Clinton do right, and why has it gone so wrong in just ten years? But first, some Cliff Notes…

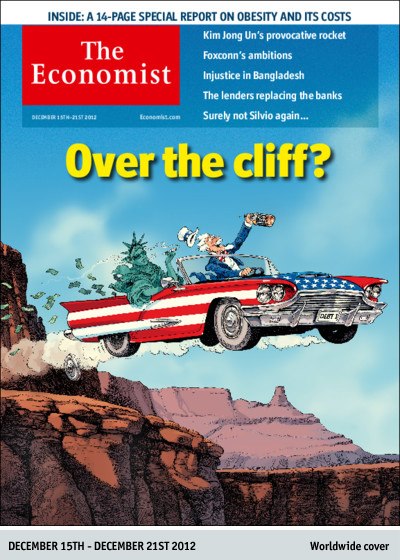

The Cliffs of Washington

There is a cliff, whose high and bending head

Looks fearfully in the confined deep;

Bring me to the very brim of it…

– William Shakespeare, King Lear

The Economist has estimated that the combination of tax increases and spending cuts that automatically go into effect on January 1, 2013, should no agreement be reached by Congress to extend Bush era tax cuts or postpone spending cuts, is worth up to 5% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The growth of United States’ economy is slowing and is expected to be as little as 1% in the fourth quarter of 2012. This sets the stage for a possible 4% contraction in the economy in the first quarter of 2013. The Journal of Accountancy observes that…

Rarely has there been such a major difference between the laws in effect one year and the next. The maximum income tax rates next year could be as high as 43.4% on ordinary income (44.6% if the potential impact of reinstated limitations on itemized deductions is taken into account) and 23.8% on long term capital gains (or 25% if itemized deduction limitations are factored in). In addition, unless Congress acts, millions of additional taxpayers will be liable for the alternative minimum income tax (AMT) for 2012 because the most recent AMT patch expired at the end of 2011. Further, the current 2% payroll tax holiday is scheduled to expire at the end of this year…In addition to the new 3.8% Medicare surtax on net investment income, starting in 2013 a new 0.9% Medicare surtax will apply to wages and self-employment income of taxpayers with MAGI [modified adjusted gross income] in excess of…threshold amounts.

This is what Ben Bernake, the chairman of the Federal Reserve, has called a fiscal cliff. It is not a sheer cliff, but you can expect the ride to get bumpy. But really, it has been all downhill since the year 2000. Rather than heading off a cliff, we are charging into a valley in the Crimean peninsula. You know the bit by Tennyson (which doesn’t end well):

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!’

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldier knew

Some one had blundered:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die,

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

So I thought the thing to do was to take a look at the numbers and try to figure out what changed since Bill Clinton ran the show in 2000 when the Republicans were just a bunch of sex-obsessed obstructionists. You remember Kenneth Star?

Methodology

I obtained various spreadsheets from the Office of Management and Budget and combined them into an historical record of federal receipts and expenditures for the last fifty years. Those intrepid enough to wade though the detail can download the spreadsheet here – US Budget – and browse the data using Excel. Perhaps you will discover your own interesting observations. I also gathered some figures from the U.S. Census Bureau and tried to correlate population trends with changes in the federal budget. Data concerning revenue primarily comes from the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). Another good source of tax data is Tax Analysts’ Tax History Project. They have a delightful section from where you can download presidential tax returns going back to Franklin Roosevelt.

Often, you’ll see historical figures adjusted for inflation. But I do not do this. I am taking what I call a “household” approach to looking at the data. You have money coming in, and money going out. As you take in more, you can spend more. But when times are lean, you need to scale back. To me, percentage comparisons are more revealing – except for this one figure to keep in mind – between 2000 and 2010, inflation accounts for a 26% increase in costs. What cost $100 in 2000, now costs $126.

My federal debt figures include debt held by the public and debt held by federal government accounts. Sometimes the media just uses the public debt figure.

My findings are presented in no particular order. They are observations, some of which bear closer scrutiny and analysis, but perhaps they point to a solution when taken as a whole.

The Findings – Revenue

First off, the “one-percent.”

In 2010, 135 million individual income tax returns were filed with the IRS reporting adjusted gross income (AGI) of $8.0 trillion on which $949 billion in income tax was paid to the government. Most (47.4% in 2011) of the revenue the government takes in comes from individual income taxes. Only 7.9% of total income came from corporate taxes in 2011. In 1962, corporations contributed 20.6% of the total and individuals accounted for 45.7%. This tells you all you need to know about what has happened with corporate income taxes over the years. The lowest contribution from corporate taxes over the past fifty years was under Obama in 2009 – just 6.6%.

There were 1.4 million tax returns comprising the top 1% of individual taxpayers in 2010. These lucky few paid $355 billion in income tax, which was 37% of the total individual income taxes paid that year. The average tax rate for those in the top 1% was 23%. The highest of any income category. If your 2010 AGI was greater than $370,000 you were in the 1% club. An AGI of $162,000 put you in the top 5%. Since the 2011 budget deficit was $1.3 trillion, you could double the taxes paid by the top 1%, and it would only cover 27% of what was needed that year to balance the budget. The implication of this is that spending cuts must be the primary contributor to balancing the budget.

By contrast, Mitt Romney’s 47% (or 50% to be precise) numbered 67.5 million tax returns in 2010 and paid $22 million in income tax which was just 2.4% of the total individual income tax collected by the government. The average tax rate for this group was 2.3%. You were in this group if your AGI was less than $34,000.

The Findings – Expenses

On the expense side, the Federal budget is divided into approximately twenty categories known as budget functions. The top five budget functions, representing 80% of all expenditures in 2011, were: Social Security (20.3%), Defense (19.6%) Income Security (16.6%), Medicare (13.5%) and Health (10.3%).

The nature of expenditures under Social Security, Defense and Medicare are clear. The Income Security budget function includes a range of programs that provide cash or near-cash assistance (e.g., housing, nutrition, and energy assistance) to low-income persons, and benefits to certain retirees, persons with disabilities, and the unemployed. Housing assistance programs account for the largest share of discretionary funding in this function. Major federal entitlement programs in this function include unemployment insurance, trade adjustment assistance income support, food stamps, Temporary Assistance to Needy Families, foster care, and Supplemental Security Income. Federal and other retirement and disability programs comprise approximately one third of the funds in this function.

The Health budget function includes direct health care services programs. Other health programs in this function fund anti-bioterrorism activities, national biomedical research, protecting the health of the general population and workers in their places of employment, providing health services for under-served populations, and promoting training for the health care workforce. Some of the agencies funded in this function include the National Institutes of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, and the Food and Drug Administration. The major mandatory programs in this function are Medicaid, the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, federal and retirees’ health benefits, and health care for Medicare-eligible military retirees.

So, since 80% of all spending can be grouped into five categories, how has each category fared from 2000 to 2010? The category experiencing the largest percentage increase in expenditures was Income Security. This category increased by 145%. As noted above, inflation over roughly the same period would have caused costs to rise by just 26%. Within the Income Security category, unemployment compensation was up a staggering 596% and food and nutrition assistance rose by 193%. Presumably, these increases have something to do with the Great Recession. This implies that a return to Clinton era levels of expenditure, once the economy improves, is not unreasonable.

The second highest increase in expenditures was seen in national defense which rose by 136%. Although it may surprise you to know that as a percentage of total government expenditures, the highest level of spending on national defense was during the Kennedy administration when defense accounted for 49% of the budget in 1962 – think Cold War. Now, defense represents 19.6% (2011) of the federal budget. The lowest level of defense spending in the last fifty years was during the Clinton administration (16.1% in 1999). Clearly, this figure can come down as the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan wind down. The Clinton era level is again not unreasonable.

Medicare came just behind defense with an increase of 129% over ten years. Most of the spending in this category consists of payments for Medicare benefits. Since 1960, the median age of the U.S. population has risen from 29.5 to 37.2 years. As a percentage of the total population, those aged 65 and over have increased from 9% to 13%. By 2050, the projection is that this age bracket will represent 20% of the population. Is there a correlation between the increase in Medicare payments and the aging population?

Since 2000, the number of people aged 65 and older rose by 15%. I previously noted that inflation can account for an increase of 26% in expenses. These two factors get us nowhere near 129%. There appears to be a problem with cost control, and this is the main problem with health care reform. The entire industry must be redesigned – but not by Congress. We have Medicare, Medicaid and now Obamacare, with fifty separate state insurance exchanges soon to be in operation. Think of the cost savings and efficiency that could be achieved by putting everyone under one system. But this is a subject for another blog…

Social Security increased by 73% over ten years which seems mild compared to the other increases. But there is this question about solvency. Historically, payments coming into the Social Security trust funds have exceeded the benefits paid out. Which is a good thing. But the problem is, the government has been borrowing from these surpluses to help fund budget deficits. As of 2011, nearly $2.7 trillion has been borrowed from the trust fund to use for other purposes. Payroll taxes fund Social Security. But payroll taxes are only levied on the first $113,700 (in 2013) of annual wages. One solution to improving the solvency of Social Security is to increase the wage base upon which the tax is levied.

The final category comprising 80% of all expenditures is Health. This budget category rose by 139%, but I place it fifth, because it only represents 10.3% of total expenditures. The comments regarding cost control under Medicare are applicable here.

The Debt

National debt figures are usually presented as a percentage of GDP. This makes sense, and is what banks do, or at least are supposed to do, when they give you a mortgage. Banks determine what percentage your mortgage payment represents to your total income in order to get an indicator of your ability to pay your debts. It is the same with governments. The credit worthiness of a nation can be determined by its debt to GDP percentage, its prospects for growth, the efficiency and fairness of its tax system and the interest rate it has to pay on new debt.

Greece, for example, is a terrible credit risk. Its economy is in depression. There are no prospects for growth, its citizens have made an art form out of tax evasion and it has high borrowing costs. Yet, the European Central Bank continues to lend it money. Spain is headed in the direction of Greece as is Italy – although Mario Monti has done an admirable job of addressing some of Italy’s issues. But if Silvio Berlusconi gets back into power, they’ll be talking about rearranging deck chairs.

The United States has had the kind of luck with its national debt that even the Irish would envy. Interest rates on U.S. Government debt have been essentially zero after factoring in inflation. In fact, some issues from the Treasury have had negative real rates of interest. In other words, you have to pay the government interest for the privilege of lending it money, rather than the other way around. The U.S. is a good credit risk despite the fact that it has hit 100% of debt to GDP. We have been there before and have prospered since.

In 1946, just after World War II, U.S. debt was 121.7% of GDP. But, realizing that a war should be paid for and that debt should be paid down, the top marginal tax rate was set at 94%. Compare this rate with the current top rate of 35%, even though we are approaching a similar debt level to that of World War II. Historical experience suggests a top marginal rate of at least 50% if the debt is to be reduced. Wars cost money, and a combination of borrowing and high taxes helped foot the bill for World War II. Top tax rates were kept high after the War and only began to drop in 1964 under Johnson once the debt had declined to 39% of GDP. The top marginal tax rate was reduced further in 1982 to 50% under Reagan, and again five years later to 38.5%.

Conclusion

Like the cliff in King Lear, the fiscal cliff is imaginary. Taxes can increase and spending can be cut without ruinous consequences. The goal is to get to $1.3 trillion in a combination of spending cuts and tax increases based upon our current deficit.

On the revenue side, the rich do need to pay more. Since the end of World War II, they have seen an almost constant decline in their top marginal rate (see the next blog – Plucking the Goose). The goal should be to generate additional revenue of $350 billion from those with AGIs of $500,000 or higher. Obama’s $250,000 AGI figure sets the bar too low.

Similarly, corporations should pay their fair share of tax for the privilege of doing business in the U.S. Somehow, corporations have managed to convince national and local governments that they are blessed when a business locates in their domicile. It should be the other way around. Consider the benefits of doing business in the U.S. – a vast capital market, a somewhat impartial justice system, low levels of corruption, an educated workforce and so on. This should add another $100 billion to the tally. That leaves $850 billion in spending cuts.

Taking defense back to Clinton era levels saves $330 billion after factoring in inflation. Assuming that increases in Income Security resulted from the Great Recession, a return to Clinton levels should cut perhaps $170 billion when the economy improves. Social Security should not be touched (since I would like to retire at some point), except that the wage base on which the tax is assessed can be adjusted upward as needed to address solvency. The government should also treat the Social Security trust fund as a true trust fund and not dip into it whenever they like to pay for other things. The big question is whether Medicare and Health services can be brought back to Clinton levels. If they can, this gives us the remaining $350 billion that is necessary to balance the budget.

It seems clear that all government health programs (Medicare, Medicaid, Obamacare) should be consolidated under one program. Cost control must also be a priority. The fiscal health of the country depends upon the health of its health care system.

Here’s to your good health in 2013! More later…